kwm

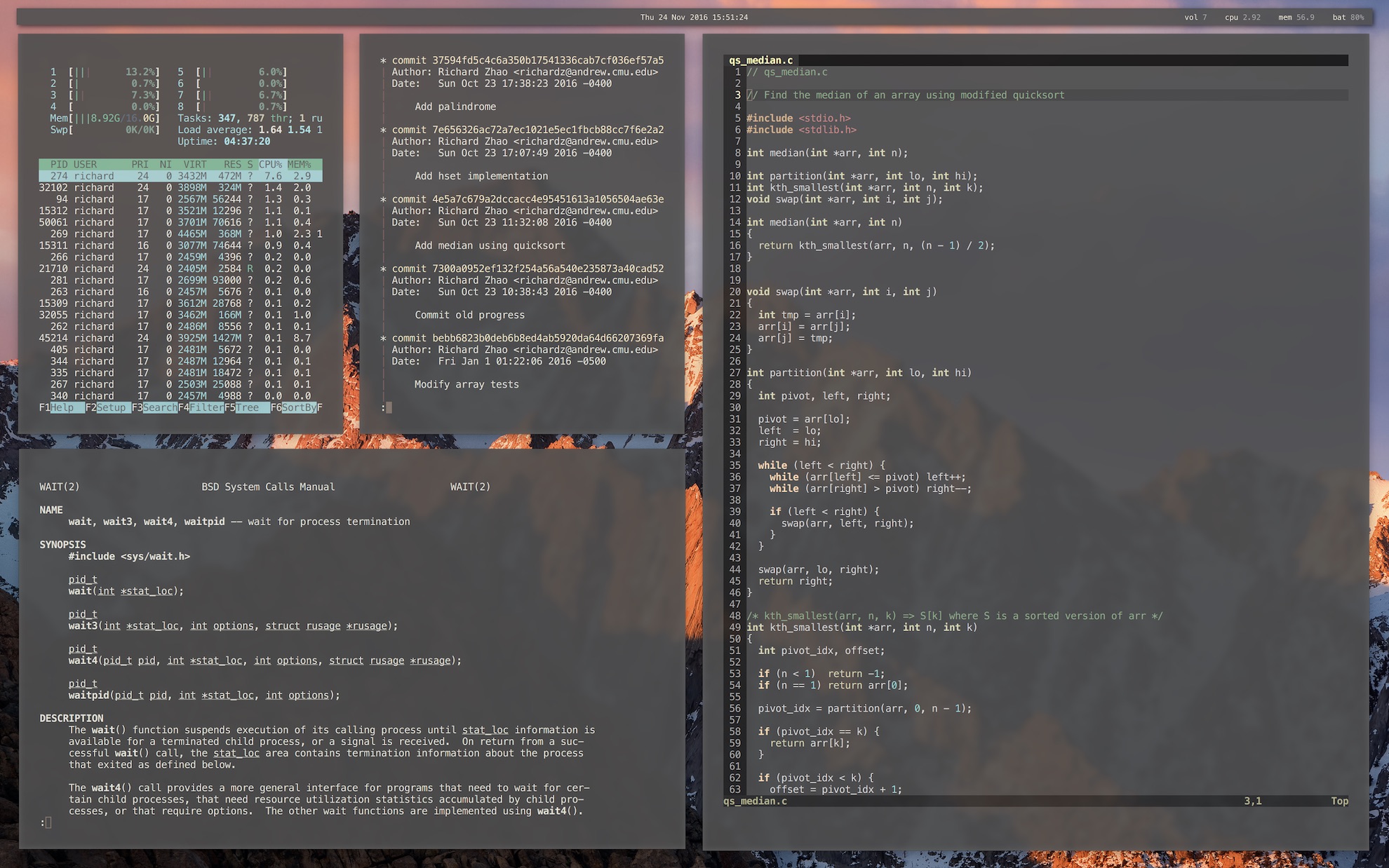

macOS’s default window manager leaves much to be

desired. kwm is a highly configurable

tiling window manager. This is a beginner’s guide to installing and configuring

kwm and khd, which provides a keybinding interface.

Architecture

kwm runs a daemon (i.e. background process) that detects windows and performs

actions on them. Actions include things such as focusing, moving, resizing, and

swapping. Since it is continuously running, kwm maintains an internal

representation of your window positioning based off a set of rules.

This differs from other styles of window management, in that if you manually

modify a window (e.g. by dragging a corner or side), kwm will resist your

change and resize it to what it thinks is its correct position. In most cases,

kwm will tile the windows on each workspace to fill the screen.

Another thing that kwm does differently is keybindings. Unlike other macOS

window managers, it doesn’t come with a set of keybindings. kwm reads from a

set of rules and tiles windows automatically. You do not have to tell it to

split a screen between two windows, or maximize a certain window. It just goes

ahead and does it on its own.

Once the workspace is managed, however, you would probably like to perform

actions such as moving focus, swapping windows, and switching spaces. That is

the purpose of khd. Like kwm, khd is also a daemon, but instead of working

with windows, it manages keybindings and communicates with kwm.

Installing kwm

Though kwm used to have a more involved installation process, the authors have

now provided Homebrew port which greatly simplifies the process.

$ brew install koekeishiya/kwm/kwm

Note that kwm requires ‘Displays have separate spaces’ enabled.

To activate the daemon, and have it run automatically at login,

$ brew services start kwm

Note that sudo should not be necessary. After kwm starts up, your workspace

should be tiled automatically. A restart may be necessary in some cases.

kwm configuration

To get started, copy the example configuration into your home directory. You can

see where the example file is located by running brew info kwm.

$ brew info kwm

...

Copy the example config from /usr/local/Cellar/kwm/4.0.2/kwmrc into your home directory.

mkdir -p ~/.kwm

cp /usr/local/Cellar/kwm/4.0.2/kwmrc ~/.kwm/kwmrc

Open the kwmrc file and take a look. Each configuration begins with the kwmc

prefix followed by a number of arguments. A detailed description of every

possible option can be found on

the wiki.

I’ve found that the defaults are generally pretty sane. Out of personal

preference, I’ve chosen to disable focus-follows-mouse and blacklisted a few

applications that I did not want to be tiled (e.g. Photoshop, Archive Utility,

Finder, and System Preferences). Additionally, I’ve set the default focus color

to transparent (0x00000000), which I’ll describe soon. Note that the colors

are in 0xAARRBBGG format.

Adding keybindings

To add keybindings to kwm operations, you’ll need to install and configure

khd.

$ brew install koekeishiya/khd/khd

$ brew services start khd

Similar to kwm, we use brew services to manage the khd daemon. I needed

to restart until khd was working, but your results may vary. One way to check

if the desired processes are running is to run

$ ps -ax | grep khd

45031 ?? 0:01.23 /usr/local/Cellar/khd/1.1.0/bin/khd

...

If khd is up, you should see an executable in /usr/local/Cellar/khd show up.

Introduction to modal keybindings

khd is a modal-hotkey daemon. Modal means that at any time, you may be in any

one of several modes, and the actions of each keybinding is dependent on the

current mode. If you use vim, you may already be familiar with modal

keybindings. Otherwise, the concept may be fairly new.

First, we’ll lay out the general idea of what we want our keybindings to

accomplish, then we’ll walk through how to implement our system in khd.

Our ‘modes’

We will begin with three modes: default, switcher, and swap.

default

The default mode is meant to be the resting state of our system. In default

mode, pressing keys shouldn’t interfere with the applications we’re using. If

you are a vim user, we are aiming for something akin to normal mode (no

editing capability).

default mode should have a single keybinding to enter a different mode with

more functionality. We’ll call it switcher.

switcher

We’ll use switcher mode to do a lot of things. First, we want to be able to

switch focus between windows. We’ll also switch focus between spaces

(i.e. virtual desktops) and throw windows from one space to another. At the end,

we’ll add a few extra functionalities such as opening new terminal windows.

Finally, from switcher mode, we will have the option to enter swap mode.

swap

In swap mode, we can make ‘edits’ to our window layout by swapping the

positions of windows and rotating the entire workspace. This is like vim’s

insert mode.

Define our modes

So, inside of a file named .khdrc, which should be located in your home

directory, we first define our three modes, and assign them colors. The colors

will be displayed by the border around focused windows.

# Enable kwm compatibility mode

khd kwm on

# Set mode colors

khd mode default color 0x00000000

khd mode switcher color 0xddbdd322

khd mode swap color 0xdd458588Choose a prefix key

To switch from default into our other modes, we’ll need a prefix. Ideally, a

prefix should be quick to type. I’ve remapped the caps key to trigger

f19, which I’ll be using as my prefix. This can be done easily using

Karabiner Elements which is

available for macOS Sierra (f19 is keycode 80, or 0x50).

Define mode switching

Now, we’ll define a way to switch between modes. There is a lot of freedom in how to do this, so definitely use what you feel is the most natural.

Starting from default mode, we will switch into switcher mode by hitting

the prefix key (keycode 0x50 in my case).

In switcher mode, we will define a single press of s to get us to swap

mode.

Finally, if we are either in swap or switcher, a single press of the prefix

should take us back to default. To make this work, the configuration looks

like

- 0x50 : khd -e "mode activate switcher"

switcher - 0x50 : khd -e "mode activate default"

swap - 0x50 : khd -e "mode activate default"

switcher - s : khd -e "mode activate swap"We can see that the syntax of a keybind is <keysym> : <command> where

<keysym> is composed of the mode name, followed by a -, and then a literal

(s), or a keycode (0x50).

To test out our mode configuration, we need to reload .khdrc. The easiest

way to do this is

$ brew services restart khd

So we can walk through how this configuration captures the behavior we desire.

Assuming we start in default mode, a single press of caps (which

triggers 0x50) brings us to switcher mode. If we want to leave, another

press of caps takes us back to default mode (this logic is captured

on the second line).

In switcher mode, pressing s gets us to swap mode (line 4). In

swap mode, pressing caps gets us back to default mode (line 3).

switcher functionality

Now, we are ready to actually add some functional keybindings. The commands

triggered by these keybindings are all prefixed with kwmc, which is a program

that can interact with kwm, the actual window manager. You can type these

commands individually into a terminal, and observe the expected behavior.

# Switch focus

switcher - h : kwmc window -f west

switcher - l : kwmc window -f east

switcher - j : kwmc window -f south

switcher - k : kwmc window -f north

# Switch to space n

switcher - 1 : kwmc space -fExperimental 1

switcher - 2 : kwmc space -fExperimental 2

switcher - 3 : kwmc space -fExperimental 3

switcher - 4 : kwmc space -fExperimental 4

switcher - 5 : kwmc space -fExperimental 5

switcher - 6 : kwmc space -fExperimental 6

switcher - 7 : kwmc space -fExperimental 7

switcher - 8 : kwmc space -fExperimental 8

switcher - 9 : kwmc space -fExperimental 9

# Throw to left/right space

switcher + shift - left : kwmc window -m space left;\

kwmc space -fExperimental left

switcher + shift - right : kwmc window -m space right;\

kwmc space -fExperimental rightSo in switcher mode, pressing h will switch focus to the left

neighbor of the current window. Pressing 3 switches to the third

space, and shift + left throws the currently focused

window left one space.

swap functionality

# Swap windows

swap - h : kwmc window -s west

swap - j : kwmc window -s south

swap - k : kwmc window -s north

swap - l : kwmc window -s east

# Rotate

swap - r : kwmc tree rotate 90In swap mode, pressing h swaps the currently focused window with

its neighbor to the left. Pressing r performs a rotation of all

windows on the workspace. The name of the command, tree rotate comes from the

way kwm represents window tilings internally–as a binary-space-paritioning

tree.

New Finder/iTerm windows

A common action that you may want to perform is opening a new Finder or iTerm window. First, consider the following two scripts:

# ~/bin/iterm.scpt

tell application "iTerm2"

create window with default profile

end tell# ~/bin/finder.scpt

tell application "Finder" to make new Finder windowWe can bind these scripts to quick keybindings in switcher mode using

switcher - return : osascript ~/bin/iterm.scpt

switcher - n : osascript ~/bin/finder.scptHyper key (untested)

As of the writing of this article, the typical way of using the caps key to trigger cmd + alt + ctrl + shift is not yet possible because Seil and Karabiner are not released for macOS Sierra.

As mentioned

before, Karabiner Elements can

still be used on macOS Sierra to rebind caps to f19. Then,

the following configuration in .khdrc may be a possible way to trigger our

hyper key

- 0x50 : khd -p "cmd + alt + ctrl + shift"which uses khd -p to simulate our desired keypress. Note that I have not yet

tested this method, but it seems plausible.

Wrap up

Hopefully this article was a helpful introduction to the world of macOS window

managers. Using a window manager may not be for everyone, but the ones who do

rarely look back. My full configuration of kwm can be found in my

dotfiles.

kwm is just one of many solutions, and I encourage you to find whatever system

works for you. It still has a few kinks (such as occaisional window

oscillations) but mostly feels stable. It’s greatest strength, configuration,

may be its greatest weakness, especially for users who don’t need or don’t

want the level of customization it provides.

But for the right person, kwm is a refreshing blend of functionality,

configurability, power, and elegance.